Shoji Kawamori appeared at Otakon 2018, which took place on August 10th through August 12th. On Otakon’s first day, Kawamorio gave a panel presentation on mecha designs and original concepts. On the second day, Kawamori gave another panel presentation on the history of Macross. Below is a transcription of Kawamori’s first panel, with the second panel’s transcription to appear at later date here on Macross World. Here’s a special thanks to Kawamori for taking the time out of his busy schedule to appear at Otakon and to the Otakon staff for hosting him!

Shoji Kawamori’s speech is copyright Shoji Kawamori.

Shoji Kawamori’s panel interpreter: Takayuki Karahashi

Transcribed and adapted by TheLoneWolf

Editor’s Note 1: Shoji Kawamori’s speech was accompanied by a slide show that he created. Since Kawamori requested that the audience refrain from taking pictures of his slides, the images shown here are approximations that I found on the Internet based off my memory. I’ve omitted images if I couldn’t find a picture faithful to the original, if the text description is fairly self explanatory, or if I’ve forgotten what was shown. For Kawamori’s second speech, I made sure to bring a notebook to write down the details of the slides.

Editor’s Note 2: Whenever Kawamori mentioned Kazutake Miyatake, he always used honorifics with his name (eg: Miyatake-san). Since this was the only person that Kawamori did this with, I’ve purposely left those honorifics intact.

(“Lion”from Macross Frontier is playing in background)

Takayuki Karahashi: In our first day (of Otakon), this fine day of August 10th 2018, we have one of our best guests, Shoji Kawamori.

(audience applause)

Shoji Kawamori: (speaking in Japanese to Karahashi) Excuse me.

Karahashi: (speaking to Kawamori and the audience) Hi, how are you, right? I’m not the guest.

(audience laughter)

Shoji Kawamori: (speaking in English) Hi everybody!

Audience: Hi!

Kawamori: (speaking in English) My name is Shoji Kawamori.

(audience applause)

Karahashi: Shall we begin? And I just wanted to make a house rule: photography is ok, but please refrain from flash (photography). And no recording of the slides, only photographs of Mr. Kawamori or the stage.

Kawamori: Today I’d like to talk about mecha designs and original concepts. And tomorrow I’d like to talk about the history of Macross, all the behind the scenes stories. So if you can come to my panel again, we’ll talk Macross tomorrow.

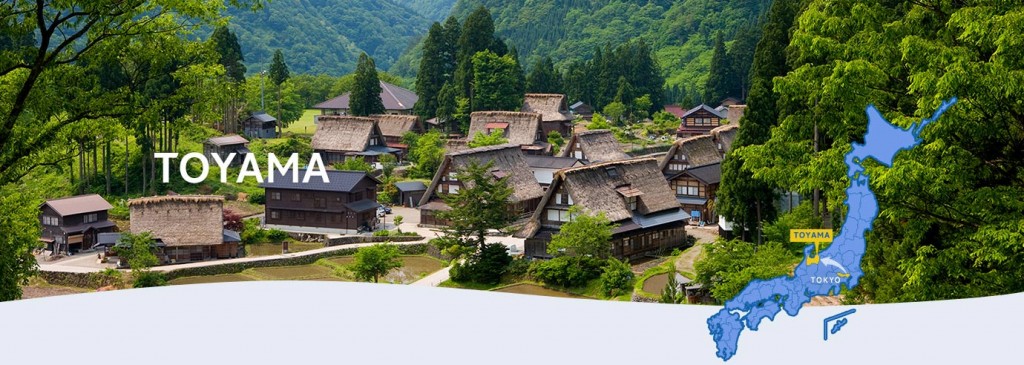

(photo: Hokuriku X Tokyo – www.hokurikuandtokyo.org)

I’d like to start talking about the overview of my life. I was born in this remote village, in a place called Toyama Prefecture in Japan. This was really a remote place in Japan. In winter, it snowed so much that you’d have to leave the house from the second floor (audience laughter). I lived in Toyama Prefecture until I was three. And when I was three, I moved to a place called Yokohama; this is the third largest city in Japan. So when I first moved from the country to the city, I was very shocked to see modern inventions, such as steam locomotives and luxury trains. This was my first “deculture!”

I got into a show called Thunderbirds when I was in first or second grade. I was very excited to see forward-swept wings and detachable container compartments. I was always a strange child; I was too proud to build model kits. I was building my own models with newspaper and paper. My father worked at an auto parts manufacturer and when I was in 2nd grade, I was very impressed by one of his cars, the Isuzu 117 Coupé. I was told by my father that this was designed by an Italian designer. So when I was in 2nd grade, I realized that the designer does have an influence on the finished product. And my next big influence was the Apollo project. I was in 3rd grade when I was watching the Apollo landing on a tiny black and white screen, watching Neil Armstrong land on the moon. And I was really furious. Why wasn’t I the first one on the moon!? (audience laughter) And this is another influence from my father.

(photo: fischertechnik – www.fischertechnik.de)

(photo: fischertechnik – www.fischertechnik.de)

He bought me this box, these are German blocks from the company fischertechnik. These do resemble Legos, but they have many more movable parts compared to Legos, so they were much more expensive. So he only bought me limited parts. And this was also when I was in 2nd grade. Because there were so few parts, I had to come up with a transformation mechanism so that I could enjoy making variations based on the few parts that I had. And this (slide) is a “revival” product of fishertechnik. Since I remembered how I assembled all my kits, I rebuilt them.

[slide: A “revival” edition of fischertechnik blocks]

[slide: A dōjin that Kawamori and his friends worked on in high school]

Okay, onto my high school days. When I was in high school, I had quite a few artistically talented friends, so we got together and made our own manga. I wrote the story and did the mecha designs. And that’s around the time when I started going to this place called Studio Nue. I started working there part-time. I had my pro debut when I was in my 2nd year of college. About half a year after I became a professional, they gave me work designing for Diaclone; I was 19 back then.

(scan: Transformerland – www.transformerland.com)

(scan: Transformerland – www.transformerland.com)

One of the sub-series under Diaclone was the Car Robot series; this eventually became The Transformers and I got to do a couple of designs for this line. It was fun to design these transforming cars that would turn into robots, but since I was an engineering major, I wanted to design real cars and real planes. I was disappointed to see that the driver’s seat, or the cockpit, would disappear when the car transformed into a robot.

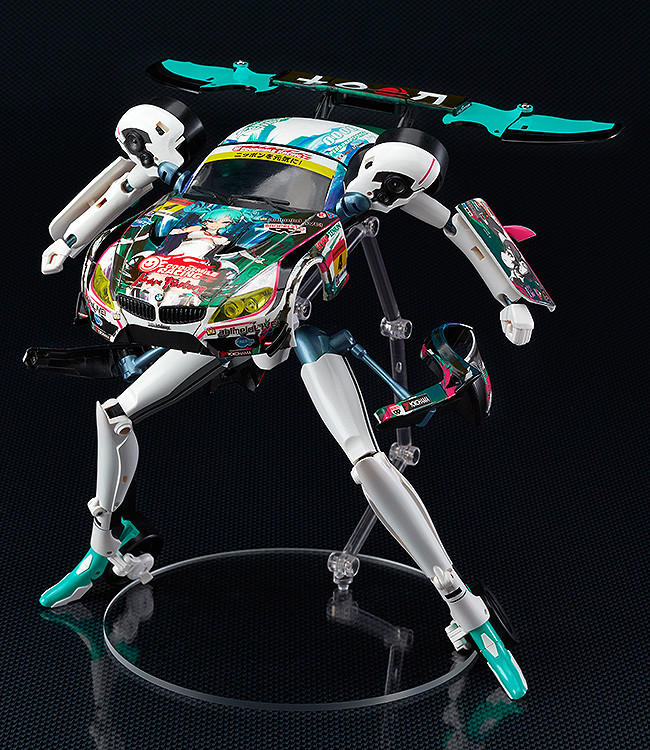

(photo: Good Smile Company – www.goodsmile.info)

(photo: Good Smile Company – www.goodsmile.info)

So this was a project that I did a couple of years ago. It’s a collaboration with Hatsune Miku where the car would transform into a robot – the driver’s seat is still there on the robot! And the prototype for this design is on the next slide.

[slide: A prototype Hatsune Miku GT Project]

I cut apart a plastic model and used Lego parts. And this completely transforms.

Next year will mark the 40th year since my career debut, so I’d like to give an overview of the works that I’ve done as a professional.

Karahashi: (addressing the audience) If you could refrain from taking any videos of the presentation.

(video: A montage of Kawamori’s work throughout the decades, accompanied by the song “Lion” from Macross Frontier)

(audience applause)

Kawamori: (in English) Thank you.

Next, I’d like to talk about originality. When I’m designing something, creating something, I value originality. My style is that I always want to be doing something that’s different from other people. And I think there are two major types of originality: one is the originality that’s quite revolutionary, something that’ll rewrite the map and that’s inspirational. And the other one is more based on personal, personality, personal creativity and personal originality.

There are several traits that I value. We’re limited in time today, so I’d like to pick a select few. One is to have various, different perspectives. When I was a child, I loved to play in the forest, so I climbed up trees a lot. When you go up in a tree, your perspective of the world really changes (Kawamori stands on his chair). And conversely, you can also look at the person up on the tree from below. And unlike a perfectly, safely built playground, when you’re going up a tree, there are certain undesigned features, such as tree branches breaking on you. And this little bit of risk is something that’s important, because that’s when your brain actually starts to function. I really do think that this is the perfect opportunity, when your brain is active, that you can come up with great designs.

So here’s an example of changing perspectives. Do you know what this is?

(photo: Rapesco – rapesco.com)

(photo: Rapesco – rapesco.com)

This is a tape dispenser. And it has weight, so that it’s meant to be really stable. But let’s look at this table object from a different plane.

(rotated photo: Rapesco – rapesco.com)

(rotated photo: Rapesco – rapesco.com)

And now you get a sense of instability, like this might roll away and not touch the ground properly. So based on that kind of concept, you can come up with a design like this:

[slide: A futuristic battleship drawn by Kawamori based on the upside-down tape dispenser]

And this was the kind of practice that I would always put on myself when I was young. So I would look at the video equipment on this table (Kawamori looks at the document camera on his panel table) and try to come up with a mecha based on that concept.

And here’s a real life work example. This was when I was around 20, coming up with an idea for a non-humanoid robot as the main character. It was really difficult to come up with something that would be suitable as a lead mecha, yet be unique and not humanoid. And my senpai at Studio Nue, the mecha designer Kazutaka Miyatake, the one who did all the designs for Space Battleship Yamato and also the Japanese version of Starship Troopers (OAV); I raced Miyatake-san to be the first to come up with the best mecha. It was like Isamu and Guld from Macross Plus racing each other to be the best. And neither of us could come up with anything decent after a whole year of trying. Since I was still a student back then, I said “I need a break, I need to go skiing with a friend.” So I went skiing. Then I’m skiing down (Kawamori stands on his chair and goes into a skiing stance), and that’s when I got the inspiration! Normally a robot is standing like this (Kawamori stands straight up on his chair). But when you’re skiing, your stance is like this (Kawamori again goes into a skiing stance). I thought it would be fresh if I could come up with a robot that had bent knees. But if you just have a humanoid with bent knees, you just have a humanoid with bent knees. So I changed perspectives and flipped the direction of the knee joints. And that’s when I came up with the idea of the gerwalk.

[slide: A picture of Kawamori’s first mecha that featured gerwalk legs]

The funny part was that when I got home from my ski trip, I told Miyatake-san “I had an inspiration!” And Miyatake-san also said “I had an inspiration!” So it turned out that I came up a two-legged gerwalk; Miyatake-san had the idea of a four-legged gerwalk. Miyatake-san always said that hand drawn animation requires as few lines as possible and was always scolding me because my mecha designs had too many lines. And that’s why my two-legged gerwalk was the winner! And there was another inspiration for the gerwalk, and that came from concepts that were in my subconscious.

[slide: A picture of Kawamori’s parakeet]

That was the parakeet that I had at home. It was a very talkative parakeet. So the idea that we can communicate across species is another concept born from my pet.

Next, on to the use of the subconscious (in original concepts). In normal life, we are constantly looking at various objects. And everything you see is consciously or unconsciously input into your subconscious. I have an example that I speculate is a product of the subconscious. Let’s look at the Tie Fighter from Star Wars. This was a design that really surprised me when I was a student. If you look at a Tie Fighter, it doesn’t have any thrust mechanism to propel this unit forward. I was impressed by the idea that the side panels were the propulsion mechanism. This was in a time when I made my first trip to the United States; I understood everything when I saw vehicles on the American highway.

(photo: Truck Trend Network – www.trucktrend.com)

(photo: Truck Trend Network – www.trucktrend.com)

You see semis and a lot of big trucks on the road; the Tie Fighter must have come from this design, because these shapes are flying right in front of you when you’re on the American freeways. So I truly believed that this was one of the remarkable uses of subconscious designs.

Another thing that I really value is the world view of the shows that I’m working on. I think about the time period, the stage, the locale, the purpose of the mecha or the people using it. I like to think about the theme of the show, whether the physics of the world is the same as Earth, does it have Earth’s gravity or is it zero gravity, what kind of technology do the people in the show possess? So the design varies to fit the world view. I’d like to go through examples of how a flying machine would differ, depending on the world that it’s to be featured in. So the basic Macross Valkyrie has basic Earth based aerodynamics, but it’s also used for space and it’s slightly more science fictiony than real Earth (fighter jets).

And this next vehicle I designed for Ace Combat.

This is based on the idea that the Japan Self-Defense Forces might actually be using something like this in the future, so this is based on real-world design concepts. Unlike in Macross designs, for reality based designs, you need something that’s slightly “dorky”. And that’s because in real life, there would be budget constraints in the design, and also there would be added features that would be extraneous to the original design concept that would slightly make the mechs unattractive.

Next, we have something from Aquarion.

(© Shoji Kawamori • Satelight / Project Aquarion)

(© Shoji Kawamori • Satelight / Project Aquarion)

This comes from a mythology based super-robot show, so it’s more in the fantastic base of things. We have a design that’s slightly more macho and part (inaudible) design. And here we have another example.

[slide: An early sketch of the Nirvash from Eureka Seven]

This is an early design of the Nirvash from Eureka Seven. In the Eureka Seven world, the climate is covered by particles called Trapars; these allow the flotation of heavy objects. When I heard that heavy ships can float in the atmosphere, I decided that, perhaps, robots can surf. So I told director (Tomoki) Kyoda my idea and it got greenlit.

[slide: Jūshinki Pandora]

And this is Jūshinki Pandora. This is being broadcast in Japan right now, but for the American release, I believe it’s coming in October, then you can binge it on Netflix. And the working title for the English release is Last Hope.

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

Since drones are such common objects now, everyone can think of the drone shape as a flying object. That’s the subconscious appeal that the design has now. And there are other forms of mecha in Jūshinki Pandora / Last Hope that I’d like to talk about later.

In doing actual designs, there are a couple of important factors. For example, there’s consideration for style: is it going to be much more realistic, like live-action? Or is it going to be more exaggerated, like in manga arts and style? And also, the actual filming has to be put into consideration. Do we want something that’s hand drawn in style, 3D CG or live-action with miniatures? So if we’re going to go with hand drawn style, this would be the design consideration.

[slide: Unknown. Possibly an early pencil sketch from Advanced Valkyrie]

This is a design from 35 years ago. Back then this was considered very liney, with lots of lines. But still, on each of the lines are designs, so that they would fit the human handstroke in terms of drawability. And next on to the age of 3D CG, the design would change thus:

[slide: Unknown]

So in 3D CG, I have a bit more complex shape that would be quite a chore to draw by hand.

And this is from Macross Frontier, so this is 10 years old. In the history of Japanese animation, this was in the early stages of 3D CG use in TV. And this was a time when CGI mecha would look inferior to hand-drawn mecha on TV anime. So for me, I came up with a much more complicated design that would be impossible to draw by hand, in order to compete against hand-drawn mecha.

This is how media type would affect design considerations. Is the design going to be for a television show, is it going to be for a big screen theatrical, is it for a toy or is it for a video game? These would all affect design considerations.

Total time would be the running time of the media, such as a TV show, which would be 20 minutes perhaps. A movie might have a running time of 2 hours. And contrast that to a car design. In real life, if you buy a car, not many people would buy a new car the next year, so you’ll probably have your car for a couple of years. So for a real life car, the design has to be something that you would not get tired of after a couple of years. But in contrast, a TV show mecha has to wow you in a very limited amount of time. So there are more exaggerations done for TV mecha, so that you would remember it much better. One example of that is the Aibo.

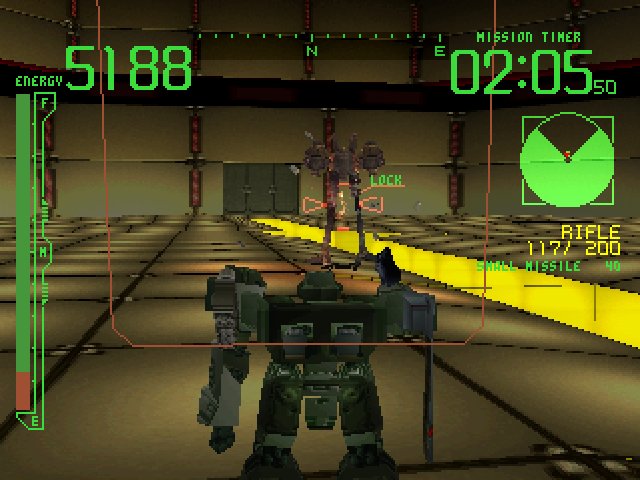

This is quite a mecha looking Aibo. And this is a design for real-world use, not quite as a toy, but really as a pet robot product. So real-world use is one of the early top considerations for the design. In the early draft, I gave Aibo a lot of opening hatches as a gimmick, but those were scrubbed. Because this was an early AI product, it was not permissible for this to walk around biting people with its opening hatch. They might be hard to make out, but there are slits on the side of the body. These were meant to be intakes for the cooling system, but the motor did not generate enough heat to require a cooling system, so this was also scrubbed. In the three earlier versions of the Aibo, when you try to catch them, they’re very slippery and hard to catch. So I put in dimples, so that you can grab it there. That’s a design consideration for real-world use. Let’s move on to an example from the Armored Core series.

This was a project that was done for the launch of the original Playstation. This was at a time when the Playstation was very much limited in the number of polygons it could use. In video games, you tend to end up looking at your robot from behind a lot. Normally you design a robot to look at it from the front, but in Armored Core and other video games, you give a lot of weight to the design of the backside of the robot. So for video game robot designs, I really make an effort so that the backside will be memorable.

(screenshot: Marvelous Inc.)

As for (more) video games, there’s something that I worked on for a title that was announced at this year’s E3. This is a new project (Daemon X Machinma) that I worked on with Mr. (Kenichiro) Tsukuda, who’s been the producer since Armored Core 2. And he’s currently at a company called Marvelous, working on titles for the Nintendo Switch. Let’s take a look at a promo video for it.

(video: A trailer for Daemon X Machinma)

(audience applause)

They’re finalizing the product for release next year. Armored Core had more of a the live-action feel to it, but since this is for the Switch, its taste is more geared towards something that’s more graphic and exaggerated, including the styles of American comics, such as a lot of heavy shadowing.

In terms of character, when you’re doing sub-mecha designs, those need to be supporting the world view of the show. But when you’re doing lead mecha, these need to be really memorable. An example of that is from Cyber Formula.

(photo: MegaHouse Corporation – www.megahouse.co.jp)

(photo: MegaHouse Corporation – www.megahouse.co.jp)

When you look at real-world auto races, such as F1 racing or the Indy 500, all the competitors end up with similar designs; that’s because everyone’s working under the same constraints. So if you show that kind of race to people unfamiliar with that, the only thing that distinguishes each racecar would be the color or the number, that’s about it. Since Cyber Formula was animated for television, each of the cars were designed so that they’re immediately distinguishable. I made sure that each car could be told apart right away, and you can tell which driver’s car is which. And the next slide is still from Cyber Formula, but from the team that has the most advanced technology.

[slide: unknown]

And this design is from 20 years ago, but if you look at the upper part, especially the (inaudible), it looks like something that modern AI designed racecars seem to actually feature. So I feel the encroachment of reality into my designs.

Another thing is that humans just don’t look at details, we also look at outlines. If you actually black out each of my figures, you can still apart what is what. When I was still in training at Studio Nue, Miyatake-san often told me, and made me, black out all my figures and try to have me tell apart all my designs. However, with modern mechs that are CGI, it might be difficult to tell them apart from silhouttes alone. But it’s one of the points that still I place onto myself as a design consideration. I make sure that each robot has a different silhoutte, so that it might have pointy shoulders or inward pointing shoulders. As for heads, it might have a pointy head or a ring on its head, so that each design is different.

For me, design basically is the major part, the main concept. I tend to use the word ‘styling’ to describe how to show the design, once the major concepts are put in. So if I liken design work to mecha designs to writing music, the design work is the composing part and styling is the arrangement part. An example of that is this.

So this is from Macross Frontier. The basic concept is the VF-25, which is the new form of trasformation (for the mecha). And from this, you could come up with different arrangements, such as the VF-27 or the YF-29. And visually it would look like this.

So the basic torso is still the same, the variations would come with with whether there’s a sub-engine, the direction of the wing, how closed the canopy might be. So it’s the same design, but the style is different in the presentation. And in humanoid form, it would look thus. I made sure that the silhoutte outlines of the mechs would each look different, so that you can tell them apart.

Ok, that’s it for design. Now I’d like to talk about my new show that’s slated for release this fall in America.

[slide: a promotional poster for Jūshinki Pandora]

(audience applause)

Jūshinki Pandora takes place in the near future, perhaps 10 to 20 years into the future. And this is in a time when there was a quantum reactor accident that ends up fusing machine AI and organic life together into a form called B.R.A.I. This is a time when humanity, in order to survive, created the “absolute defense city” and they live inside that in a very subsistent way. In our real world, the advances in AI are progressing so rapidly that humans are losing against AI in games such as Shogi, Chess, and Go. But there are still lots of shows that feature AI in the form of entertainment, so this is me doing it in a form of robot entertainment with the menace in the form of B.R.A.I.

It was predicted that in the near future, humans would be doing all the “brainy” work and machines would be doing all the manual work. But with such advancement in technology and AI, it seems like the reverse might be our future. The forecast is that since it costs money to develop AI, that AI work would be all the money generating work. So are we all worried that high paying jobs, such as medicine, and even art, would be taken over by machines soon? So Jūshinki Pandora / Last Hope is about the story of humanity’s desperate survival after it’s been deposed from the top of the ecosystem on Earth. The main character, Leon Lau, may look good on the poster, but as a character, he’s someone who’s completely lost in research and has no ability to lead a normal life. So just like us, he’s just an obsessed star in a small, little world (Kawamori laughs). But he looks good once he’s in battle mode (Kawamori laughs again).

So that’s the gist of the show. There are three main mecha.

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

The red one we saw earlier is the kung-fu mecha. And the center one is Leon’s mecha; this transforms into a four-wheel vehicle mode. And the first one transforms into a bike. And their transformations are thus.

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

(© Shoji Kawamori, Satelight / Xiamen Skyloong Media)

Up until now, I’ve made lots of planes and automobiles transform. Many other animated shows have transformed bikes before, so I haven’t touched that, until now. So this might be in the shape of a bike, but it’s about the size of a tank. The B.R.A.I. is very powerful and they have caused lots of destruction onto Earth, so a lot of the surface of the Earth is uneven, and this mecha is designed so it can navigate such rough terrain.

Since I’m talking about my new show, I’d like to show you the Lego model that I built as a prototype for this design (Kawamori shows the audience a Lego model of Doug Hobart’s MOEV in vehicle mode that he brought to this panel). This is the first time that I’ve shown this to anyone here in America. Can we get this up on the monitor? (The Otakon staff experiences technical difficulties in getting the room’s projector to switch over from Kawamori’s laptop to a document camera, so that Kawamori can broadcast his Lego model to the room). Since this is a prototype, it’s prone to breakage if I handle it too much. Until I reach this form of design, I try to build and then destroy, build and destroy; so Lego blocks are just perfect for prototyping designs. Normally with Lego blocks, there would be an existing real-life car or vehicle that you would try to replicate with Lego blocks. But for me, Legos are a tool for me to visualize something that doesn’t exist in reality yet. So something that you normally wouldn’t do with Legos, such as cutting Lego blocks apart or gluing Lego pieces together, is something that I actually do with my prototype building. When I’m building a Lego prototype, there are times when I would do a rough sketch first, and then build the Lego prototype based on that sketch. Or, go directly into using blocks.

(Kawamori and the Otakon staff converse about the malfunctioning document camera)

If it’s not possible to get this up on the monitor, we might run out time and I won’t get to show you the transformation gimmick. Ok then, let’s start the transformation! Feel free to come up close to the stage if you want to take a closer look.

(The audience walks up to the stage and Kawamori begins transforming Doug Hobart’s MOEV. Unfortunately, without any video to provide context, Kawamori’s dialogue probably won’t make much sense. But here it is, regardless.)

There’s three modes of transformation: vehicle mode, attacker mode, and terraroid mode. But we’ll run out of time, so I’ll go straight from vehicle to humanoid. As you can see, the form is different from left and right; there’s cover on one side and the other side is uncovered. This is because each part turns into the left leg and the right leg. So first off, this has the fuction of buffering of the uneveness of the surface (of Earth). And this would go back. And this is a feature that’s used to extend the legs. The cover opens up, the wheel turns. In the same way. And the front end bends out. This way, the wheel is showing out, but if you turn it out the other way around…These are big wheels, but they are almost hidden by the feet and you can almost not see them anymore. And the arms come out in between the engine and what looks like the wheels. So the side opens up and the arms extend. And the cockpit is here. The gun could still be carried on the shoulder but, you take this off and it becomes a handheld gun. And the key point is from here on. This swings out and swings again. And this enters this end. And the head wakes up. And these connecting parts come down. And the arms nears completion. It might be slightly hard to tell, but the left side and the right side are slightly different because they are from different drafts. The left side is closer to the final draft. This comes out and becomes a wing. This panel is slightly smaller, but it’s a just panel that’s enlarged. And this is still a prototype, so if I had success with one side, that could be replicated with computer graphics, and that would be the final draft. And there we have it in completion.

(audience applause)

So all the other units that Leon goes on to and Queenie rides are built at first with Lego prototypes. I wanted to bring the other two units as well, but since I played around with them too much, they broke. So the first unit is the only one that I managed to bring.

I wanted to show you the trailer for (Jūshinki) Pandora, but since we’ll need to reconnect the computer, maybe we can do a few questions and answers before we get to the promo.

(the audience line up at a microphone)

Attendee #1: If you got to make a third season of AKB0048, what would you put in it?

Kawamori: Well, I would very much love to get the opportunity to do a third season of AKB0048. And the story would be about the further growth of Nagisa and others til their graduation.

Attendee #2: So I’d like to say, if you did some of the mechanical designs for “hisomaso” (Dragon Pilot: Hisone & Masotan), the dragons that turn into jets? Could you talk about the designs a little?

Kawamori: This was a commission from director (Shinji) Higuchi. At first I was told it was going to be a transformation from a monster into a fighter, so I was thinking of something that was more ferocious. But as we went through production meetings, it became much more cuter. Director Higuchi told me “I want it to look like a monster cosplaying as an airplane.” But I made it so that it might actually work on a real monster, so that they can put it on and become airborne. (speaking in English) Ok ok, next?

Attendee #3: So I’m a big fan of your work, everything from Macross: Do You Remember Love?, and I would like to know what was one of your fondest memories from that project.

Kawamori: There are lots of things that I’m fond of from Do You Remember Love?, but this was my first work as a director and I was still attending college and I also had design work for three other titles at the same time, so I really remember that I was busy as hell. (speaking in English) Thank you.

Attendee #4: Hi, in your experience, have you noticed a difference between the sort of designs that people that come from an animation background come up with compared to designs that people like you, whose background is more purely design, come up with?

Kawamori: This really does depend on individual talent and style. But designers tend to value realism and how it may have a real-world design. Animators tend to value the ability to be able to easily draw some object and still “wow” an audience and carry a visual impact.

Attendee #4: (speaking in Japanese) Ah, I see. Thank you.

Kawamori: And I think we have time for one more question.

Attendee #5: Hello, thank you for being here. Why do you like transforming so much?

Kawamori: (pleasantly surprised) Let’s see, that is a very interesting question! I think it is based on my early childhood experience. I was living in the countryside of Toyama and then moved to a very futuristic city that was Yokohama. It’s like the level 1 player being thrust from his original village out to the real-world. And I think that has a lasting impression on me.

Ok, since we have the computer back, let’s take a look at the promo video for Jūshinki Pandora.

(video: Jūshinki Pandora promo video)

(audience applause)

Apologies that the trailer is not in English! But within two months we’ll have the English edition available. Thank you very much for coming today! And if you’re able to come to my panel tomorrow at noon, I’d like to talk about the history of Macross; how I came up with the idea and how that project was made behind the scenes. Thank you, really, for coming today!

(audience applause)